Public opinion on the caste census in India is multifaceted, reflecting a spectrum of perspectives influenced by social, political, and regional factors.

Support for the Caste Census

Broad Public Backing: A nationwide survey conducted by the Data Action Lab for Emerging Societies (DALES) revealed that 62% of respondents across 20 states support the caste census, while 19% oppose it. Support is particularly strong among marginalized communities, including Scheduled Castes (SCs), Scheduled Tribes (STs), and Other Backward Classes (OBCs). (The Wire)

Political Endorsements: Leaders across the political spectrum have expressed support. Prime Minister Narendra Modi emphasized that the caste enumeration initiative aims to integrate marginalized communities into mainstream society and make them central to developmental policies. Similarly, Haryana Chief Minister Nayab Singh Saini praised the initiative as a visionary move toward achieving social justice. (@EconomicTimes)

Advocacy for Social Justice: Proponents argue that the caste census is essential for identifying and addressing disparities in representation and resource allocation. For instance, OBCs constitute nearly 52% of India’s population but hold only 27% of reservations in jobs and education, highlighting the need for accurate data to inform equitable policies. (www.ndtv.com)

Concerns and Opposition

Potential for Division: Critics worry that emphasizing caste identities might exacerbate social divisions. Some argue that the caste census could hinder efforts to create a more united society due to political and logistical challenges. (The Statesman)

Data Accuracy and Implementation Issues: Concerns have been raised about the accuracy of caste data and the methodologies employed. For example, the 2022 Bihar caste-based survey faced criticism for alleged inaccuracies and underrepresentation of certain castes, leading to debates about the reliability of such data. (Wikipedia)

Political Motivations: Some view the push for a caste census as politically motivated, aimed at garnering support from specific voter bases. This perspective suggests that the initiative may be more about electoral gains than genuine social reform.

Regional Variations in Opinion

Strong Support in Certain States: States like Chhattisgarh, Bihar, Gujarat, Odisha, and Maharashtra exhibit high support for the caste census, with over 75% of respondents in favor in some areas. (The Wire)

Mixed Reactions in Others: In contrast, states such as Assam, Kerala, Punjab, Tamil Nadu, and West Bengal show more divided opinions, with support for the caste census falling below 50% in these regions. (The Wire)

Conclusion

The caste census in India is a subject of significant public interest and debate. While many see it as a necessary step toward social justice and equitable policy-making, others express concerns about its potential to deepen societal divisions and question the motivations behind its implementation. The discourse reflects India’s complex social fabric and the ongoing challenges in balancing equity, unity, and political considerations.

Indian politicians hold a range of perspectives on the caste census, reflecting diverse ideological positions and strategic considerations. Here’s an overview of key viewpoints:

Bharatiya Janata Party (BJP) and National Democratic Alliance (NDA)

Historically, the BJP exhibited reluctance toward conducting a caste census. However, recent developments indicate a strategic shift. In May 2025, Prime Minister Narendra Modi emphasized that the caste enumeration initiative aims to integrate marginalized communities into mainstream society and make them central to developmental policies. (@EconomicTimes, ThePrint, @EconomicTimes)

Haryana Chief Minister Nayab Singh Saini praised this move, calling it a visionary step toward achieving social justice and inclusive development. (The Times of India)

Despite this shift, some BJP leaders have accused the Congress of politicizing the issue. BJP chief JP Nadda stated that while the party is not against conducting a caste census, the Congress seeks to divide the country through such measures. (@EconomicTimes, www.ndtv.com)

The Rashtriya Swayamsevak Sangh (RSS), the BJP’s ideological parent, has expressed that while a caste census can be useful for welfare activities, it should not be exploited for electoral gains. (India Today)

Indian National Congress and INDIA Alliance

The Congress party has been a vocal proponent of the caste census. Rahul Gandhi has emphasized that such an exercise is essential for effective policymaking and ensuring equitable representation. The party’s 2024 manifesto pledged to conduct a comprehensive caste census and to legislate the removal of the 50% cap on reservations for SC, ST, and backward classes. (www.ndtv.com, Wikipedia)

At a rally in Jharkhand, Congress leaders credited Rahul Gandhi for compelling the central government to conduct a caste census by persistently advocating for OBC rights. (The Times of India)

In July 2023, a coalition of 26 opposition parties, including the Congress, resolved to conduct a caste census, asserting their commitment to social justice and equitable development. (The Hindu)

Regional Parties and State Leaders

Several regional parties have also expressed strong support for the caste census:

- Nitish Kumar (Janata Dal-United): The Bihar Chief Minister has been a consistent advocate for the caste census, stating that it will reveal the number of people of different classes, aiding in their upliftment. (ThePrint)

- H. Anjaneya (Former Karnataka Minister): He emphasized the need for internal reservations within SC communities and credited Rahul Gandhi’s advocacy for prompting the Prime Minister to agree to a caste census. (The Times of India)

- Tamil Nadu Parties (DMK, VCK, PMK): These parties have leveraged the move to press for increased reservations based on population data, advocating for proportional reservations for Scheduled Castes and Tribes. (The Times of India)

Critics and Cautionary Voices

While many support the caste census, some voices urge caution:(India Today)

- Upendra Kushwaha: Initially a supporter, he later criticized the Bihar caste survey as manipulated, alleging inaccuracies and calling for the socio-economic profile data to be made public. (Wikipedia)

- RSS: As mentioned, the organization supports the caste census for welfare purposes but warns against its use for political campaigning. (India Today)

In summary, the caste census has garnered support across various political spectrums, with proponents viewing it as a tool for social justice and equitable policy formulation. However, concerns about potential politicization and data accuracy persist among certain leaders and organizations.

The 1911 Census: Introduction of the “Ten Tests” for Identifying ‘Untouchables’

In an effort to systematically identify and enumerate communities considered ‘Untouchable,’ the 1911 Census introduced a set of ten criteria, commonly referred to as the “Ten Tests.” These tests aimed to delineate ‘Untouchables’ from other Hindu castes based on religious practices, social interactions, and ritual status. The criteria included:(Mooknayak, surajyengde.com, Manupatra)

- Denial of the supremacy of Brahmins.

- Absence of initiation (Mantra) from recognized Hindu gurus.

- Rejection of the authority of the Vedas.

- Non-worship of major Hindu deities.

- Exclusion from services by ‘good’ Brahmins.

- Lack of Brahmin priests.

- Denial of access to the inner sanctums of Hindu temples.

- Association with pollution, either by touch or proximity.

- Practice of burying the dead instead of cremation.

- Consumption of beef and lack of reverence for the cow.(surajyengde.com, Manupatra)

These tests were applied inconsistently across regions, leading to conflations between economically or educationally disadvantaged groups and those subjected to social untouchability. This lack of uniform application resulted in skewed data and misrepresentations of certain communities. (Mooknayak)

Distinction Between ‘Untouchables’ and ‘Caste Hindus’

The 1911 Census’s categorization efforts highlighted a significant distinction between ‘Untouchables’ and ‘Caste Hindus.’ While ‘Caste Hindus’ encompassed the traditional varna hierarchy—Brahmins, Kshatriyas, Vaishyas, and Shudras—’Untouchables’ were positioned outside this framework, often subjected to systemic social exclusion and discrimination. This differentiation was not merely social but also had political implications.(Manupatra, Janata Weekly)

For instance, in 1910, Muslim leaders submitted a memorandum to the British government, advocating for the separation of ‘Untouchables’ from the Hindu population in political representations. They argued that ‘Untouchables’ should not be counted within the Hindu fold, thereby affecting the allocation of political representation and resources. (Mooknayak, surajyengde.com)

Implications and Legacy

The 1911 Census’s approach to caste categorization had lasting impacts on Indian society and its understanding of social hierarchies. By institutionalizing the concept of ‘Untouchability’ through official enumeration, the census reinforced social divisions and provided a framework that influenced subsequent policies and social reforms.(Mooknayak)

Dr. B.R. Ambedkar, a prominent social reformer and architect of the Indian Constitution, utilized data from the 1911 Census to advocate for the rights and representation of marginalized communities. The census’s findings underscored the need for affirmative action and legal protections for those subjected to systemic discrimination.

In summary, the 1911 Census’s introduction of the “Ten Tests” for identifying ‘Untouchables’ marked a significant moment in colonial India’s engagement with caste. While aiming for systematic classification, the census’s methodologies and their inconsistent application highlighted the complexities and sensitivities involved in categorizing diverse communities. The legacy of these classifications continues to influence discussions on caste, identity, and social justice in contemporary India.(Mooknayak)

1931 Caste Census of India

The 1931 Census of India stands as the last comprehensive enumeration of caste across the country, offering invaluable insights into the social fabric of pre-independence India. Conducted under the supervision of Census Commissioner J.H. Hutton, this census has since served as a foundational reference for understanding caste dynamics and informing policy decisions.(Business Standard)

Key Findings of the 1931 Caste Census

1. Caste Demographics

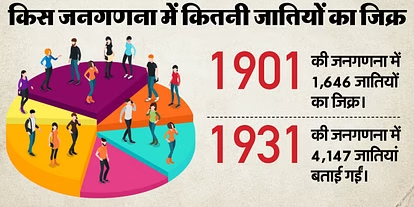

The census identified 4,147 distinct castes across British India. Notably, it estimated that Other Backward Classes (OBCs) constituted approximately 52% of the total population, which was around 271 million at the time. This statistic later became pivotal for the Mandal Commission in 1980, which recommended a 27% reservation for OBCs in government jobs and educational institutions—a policy implemented in 1990. (Wikipedia, India TV News)

2. Population Distribution by Major Castes

The census provided detailed population figures for major caste groups:

- Brahmins: Over 15 million

- Jatavs: Approximately 12.3 million

- Rajputs: Around 8.1 million

- Kunbis: About 6.4 million

- Yadavs (Ahirs): Roughly 5.7 million

- Telis: Approximately 4.3 million

- Gwalas: Around 4 million

3. Literacy Rates by Caste

The census highlighted significant disparities in literacy rates among different castes. For instance, in the United Provinces (present-day Uttar Pradesh):

- Kayasthas: Male literacy at 70%; female literacy at 19%

- Brahmins: Male literacy at 29%; female literacy at 3%

- Vaishyas: Male literacy at 38%; female literacy at 6%

- Sayyids: Male literacy at 38%; female literacy at 9%

- Bhumihars: Male literacy at 31%; female literacy at 3%(Wikipedia)

4. Sex Ratio Disparities

The census revealed notable variations in sex ratios among different communities:(The Indian Express)

- Rajputs: Lowest sex ratio at 798 females per 1,000 males

- Jats: Sex ratio at 805

- Gujars: Sex ratio at 832

- Bengali Brahmins: Sex ratio at 847

- Muslim Sayyids: Sex ratio at 884

- Nayars (Kerala): Highest sex ratio at 1,154(The Indian Express)

The census attributed these disparities more to the neglect of female children than to practices like infanticide. (The Indian Express)

Methodological Approach and Challenges

Transition from Varna to Occupational Classification

Previous censuses, notably the 1901 Census under H.H. Risley, attempted to classify castes based on the varna system, leading to widespread dissatisfaction and social unrest. In response, the 1931 Census shifted to an occupational classification system to avoid reinforcing hierarchical biases. However, this approach faced challenges:(The Indian Express)

- Regional Variations: The social status associated with certain occupations varied across regions. For example, cultivation was esteemed in northern India but linked to ‘exterior’ castes in parts of southern India.

- Fluid Caste Identities: Communities often changed their caste affiliations between censuses to seek higher social status, complicating consistent classification.

- Inconsistent Nomenclature: The same caste might be known by different names in various regions, leading to difficulties in standardization.(The Indian Express)

Historical Significance and Legacy

The 1931 Caste Census remains a cornerstone in India’s socio-political landscape:

- Policy Formulation: Its data underpinned the Mandal Commission’s recommendations, leading to significant affirmative action policies for OBCs.

- Understanding Social Dynamics: The census provides a snapshot of pre-independence India’s complex caste structures, informing contemporary debates on social justice and representation.(The Times of India)

Post-independence, the Indian government discontinued comprehensive caste enumeration in censuses, with the exception of Scheduled Castes and Scheduled Tribes. While the 2011 Socio-Economic and Caste Census (SECC) collected caste data, it was not released publicly due to concerns over data accuracy and potential social repercussions. (fortuneiascircle.com, Acqias)

Accessing the Full 1931 Census Report

For an in-depth exploration, the complete 1931 Census report is available through the Office of the Registrar General & Census Commissioner, India:

This comprehensive document encompasses detailed statistics on population distribution, literacy, occupation, religion, caste, tribe, and more across British India.

Caste Census of Indian States

The Uppara community, also known as Sagara in some regions, is a Hindu caste predominantly found in the Indian states of Andhra Pradesh, Telangana, Karnataka, and Tamil Nadu. Traditionally, they have been involved in occupations such as stonecutting, tank-digging, earth-working, and salt extraction from rocks—a practice that influenced their name, as “uppu” means salt in Telugu and Kannada .(Wikipedia)

Classification and Socio-Economic Status

The Upparas are classified as an Other Backward Class (OBC) in India, a designation that acknowledges their historical socio-economic disadvantages and qualifies them for certain affirmative action benefits .(Wikipedia)

In Karnataka, recent caste census data has shed light on the community’s socio-economic standing. The Uppara community has been identified as the most socio-economically disadvantaged among 22 specific communities in the OBC and general list, with a backwardness score of 134.88 out of 200 . Their population in the state is approximately 856,815, accounting for about 1.43% of Karnataka’s total population .(Threads, The New Indian Express)

Caste Census and Policy Implications

The Indian government’s decision to include caste details in the upcoming national census marks a significant move toward understanding and addressing the needs of various communities, including the Upparas. This comprehensive data collection aims to inform equitable policy-making and welfare schemes for marginalized groups .(AP News, Wikipedia)

In Karnataka, the caste census has already influenced policy discussions, with the introduction of a new classification system that includes Category 1A for communities like the Upparas . Such classifications are expected to play a crucial role in the allocation of resources and implementation of targeted development programs.(Hindustan Times)

Cultural and Regional Variations

The Uppara community is known by various names across different regions, reflecting a rich tapestry of cultural and linguistic diversity. In addition to “Sagara,” other synonyms include Beldar, Lonari, and Uppiliyan, among others . These variations often correspond to regional languages and occupational specializations.(Wikipedia)

Conclusion

The Uppara community’s classification as an OBC and their identification as one of the most socio-economically disadvantaged groups in Karnataka underscore the importance of targeted policies and programs. The forthcoming national caste census is anticipated to provide further insights, enabling more effective strategies to promote social equity and development for the Upparas and similar communities.(Wikipedia)

Caste Census of Indigenous Assamese Muslim and Bengali Speaking Muslim

The Assam government has initiated a caste-based census focusing on seven indigenous Muslim communities to distinguish them from Bengali-speaking Muslims, often perceived as migrants from Bangladesh. This move aims to recognize and preserve the unique cultural identities of these indigenous groups.(The Times of India, Organiser)

Indigenous Assamese Muslim Communities

The seven indigenous Muslim communities identified for the caste census are:

- Goria

- Moria

- Deshi

- Syed

- Jolha (Julha)

- Kiren

- Ujani

These communities have deep-rooted histories in Assam, with some tracing their lineage back to the 13th century. For instance, the Deshi community is believed to descend from Ali Mech, a native leader during Bakhtiyar Khalji’s Tibet campaign in 1205. The Jolha community, originally weavers, migrated to Assam during the Ahom dynasty and later under British colonial rule. They are now recognized as part of the More Other Backward Classes (MOBC) and share cultural similarities with the Tea Tribe community of Assam. (Wikipedia, Wikipedia)

Bengali-speaking Muslims in Assam

Bengali-speaking Muslims, often referred to as “Miya” Muslims, are descendants of migrants from regions like Rangpur, Rajshahi, and Cumilla during British colonial times. They primarily reside in the Brahmaputra Valley and constitute a significant portion of Assam’s Muslim population. The term “Miya” has been reappropriated by the community, especially through “Miya poetry,” to assert their cultural identity and address socio-political challenges. (Wikipedia)

Purpose of the Caste Census

The caste census aims to:(The Times of India)

- Accurately document the socio-economic status of indigenous Muslim communities.

- Differentiate indigenous groups from migrant populations to ensure targeted welfare schemes.

- Preserve the unique cultural and linguistic identities of these communities.(Telegraph India)

Chief Minister Himanta Biswa Sarma emphasized that this initiative responds to the long-standing demand of indigenous Muslims for official recognition and aims to fulfill their aspirations. (@EconomicTimes)

This move has been met with support from indigenous Muslim groups who believe it will help protect their identity amid the growing population of Bengali-speaking Muslims. (Deccan Herald)

However, some critics argue that the census could further marginalize Bengali-speaking Muslims by reinforcing divisions based on origin. The Assam government maintains that the primary objective is to ensure equitable development and representation for all communities.

For more detailed information, you can refer to the official announcement by CM Himanta Biswa Sarma on X (formerly Twitter).(X (formerly Twitter))